Wild rice

- rosemary

- Aug 6, 2025

- 5 min read

I have been reading my chosen book for book group - The Sentence by Louise Erdrich a multi-award winning author - including the Pulitzer Prize, who is ethnically a North American Indian - of the Ojibwe people who live in and around Minnesota. It's a difficult book in lots of ways, and I'm not going to talk about the book here. I'm going to talk about wild rice, because it - and many other foods actually - crops up here and there in the book.

I have never eaten wild rice. Decades ago I bought a packet, because it was trendy, but I never cooked it, and I think I threw it away. I dread to think that it is lurking in a drawer or a cupboard somewhere. But I don't think it is. So since there seemed to be things to say about it, other than a simple what to do with it approach I thought I would make it my subject for today.

First a little bit of biology. There are a few strains of wild rice, which, as you probably know is not rice - oriyza. The botanical name for its genus is zizania, although it is related to rice because zizania is a genus of the Oryzeae tribe - and so on backwards through other grass-like plants. There are four species of zizania - three from North America and one from Asia. Palustris (northern), Aquatica (Southern or Annual) and Texana (Texas) are the American ones and Latifolia (Manchurian) from Asia.

The true North American wild rice - i.e. the wild rice growing wild, is under threat due to all the usual things, pollution, climate change, loss of habitat, etc. and yet ironically in New Zealand the Manchurian wild rice has been declared some kind of official weed which makes it illegal to import, etc. Tasmania as well is keeping a very close eye on it. It seems it is difficult to eradicate, and so the current policy in New Zealand is containment rather than eradication.

By the twentieth century the food world became aware of the nutritional and taste benefits of wild rice, and also of the threats to the wild growing varieties, which made it extremely expensive if you could find it. And actually it was a good income for the Native Americans who harvested it as well.

However, in 1950 James and Gerald Godward started experimenting near Minnesota by building paddy fields in which to grow the palustris plant - a water plant, in spite of the theory that the plant needed running water. They were successful and now it is grown and processed commercially - mostly in California and Missouri, but also here in NSW and also in Hungary. Well that's according to Wikipedia, but it is probably grown elsewhere too.

Back to the Ojibwe people. Who are they?

"Ojibwe people arrived in present-day Minnesota in the 1600s after a long migration from the east coast of the United States that lasted many centuries. Together with their Anishinaabe kin, the Potawatomi and Odawa, they followed a vision that told them to search for their homeland in a place “where the food floats on water.” Jessica Millgroom/Minn Post

And so they settled one Madeline Island (Moningwanakauning) on Lake Superior. Traditionally the rice is harvested at the wild rice moon (manoominike giizis) - August and September.

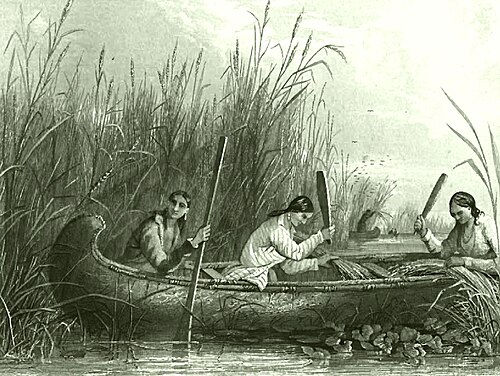

"Ojibwe people harvested wild rice, and continue to harvest it today, in pairs, with one person pushing or paddling a canoe and the other knocking rice into it with sticks (bawa’iganaakoog). When the wild rice is ripe, the grains fall easily into a canoe, and the grains that fall into the water lodge themselves into the mud, then grow into the following year’s stands of rice." Jessica Millgroom/Minn Post

"Freshly harvested manoomin is called “green” rice. When processed in the traditional way, it is parched (roasted) over a fire, then threshed by being stepped or danced on. This motion, called jigging, loosens and removes the fibrous outer covering of the grain. Finally, to separate the hulls from the grain, wild rice is “winnowed” or “fanned”—tossed up in the air with birch bark trays (nooshkaachinaaganan) so that the hulls are blown away and only the edible grain is left behind." Jessica Millgroom/Minn Post

It was a vital part of the Ojibwe people's diet and spiritually important to them as well. Hence major protests such as the current one against the Embridge Line 3 oil pipeline, which will destroy many of the plants growing places. Not to mention the loss of income from selling the rice - although I imagine the true wild-grown wild rice fetches a higher price and is therefore coveted by food snobs and gourmets.

So much for its cultivation and cultural, and historical significance. What can you do with it should you feel so inclined?

To be honest - not a lot really. Well not a lot that would be different to what you would do with rice. And because of its expense you will often find many recipes - and packets in the supermarket - in which it is mixed with brown or basmati rice. Just a few grains of the wild rice it seems to me. I did find a few things to at least get you thinking.

The first, of course, is just to cook it and eat it as an accompaniment to something else. As you would rice. You don't cook it the same however, Love and Lemons will tell you how - basically cook it in boiling water like pasta until it's done, and once drained you leave it in the pot for around 10 minutes to steam dry under a tea-towel and a lid.

And maybe this is the best thing to do with it. A bit like using any of those other ancient grains.

Indeed it seemed to me that the main ways of using it were in salads and pilaf kind of dishes: Rice salad with nuts and sour cherries - Ottolenghi/The Happy Foodie; Wild rice salad - Nagi Maehashi/Recipe Tin Eats; Wild rice with mushrooms, cranberries and chestnuts - Alecia Moore and Robbie Grantham-Wise/Food and Wine; Wild rice with citrus - Jessica d'Ambrosio/Food Network; Wild rice pilaf - Love and Lemons

There were a few stews or bakes: Classic chicken and wild rice hot-dish - Amy Thielen/Food Network; Hunter's stew with braised beef and wild rice - David Ansel/Food and Wine; and One-pot chicken and wild rice pilaf - Magdalena Roze/delicious.

And a couple of outliers, which in a way I have only included because they were different - Wild rice pancakes with cherry compote - Molly Yeh/Food Network and Cranberry-pecan wild rice stuffing/Food Network

I suspect that in this instance the stories behind the ingredient itself were more interesting than the ingredient itself, which I suspect I shall not be buying any time soon. But you never know.

YEARS GONE BY

August 6

2024 - A freezer challenge

2023 - Nothing

2022 - Greens and bread

2021 - Nothing

2020 - Missing

2017 - Nothing

2016 - Mushrooms

3 stars for the Wild Rice, 4 for the story tellinbg. Doesn't look very enticing!

Coincidentally heard a podcast last night on the problems in Caifornia where farmers there love to grow white rice, which needs heaps of water - not a commodity in Southern California, where most of the farming is irrigated. There you go. Perhaps it explains why the native American Indians grew black rice!