Beginnings

- Apr 27, 2023

- 7 min read

“Meat is used. You prepare water. You add fine-grained salt, dried barley cakes, onion, Persian shallot, and milk. You crush and add leek and garlic.” Mesopotamian recipe 1730BC

As always what I intended to write about has morphed into something else. Well I've added something else. And that addition is the above cuneiform tablet dated 1730BC and now resting in Yale University's Archives somewhere. It has been decreed the first ever cookbook and at the top of the page is one of its recipes - a recipe for a lamb stew called Me-e puhadi and shown below, because of course somebody had to make it.

A bit of a coincidence really since I was only talking about stews and how ancient they were a short time ago - and you would have to say it looks perfectly eatable, even somewhat tempting for 'brown food'.

First cookbook yes - well from what has so far been found. However, whether this was the first time that anyone made lamb stew is another matter after all. The instructions, as you can see are very brief, and the general opinion, with which I agree, is that this is because it is written for experienced cooks who could work from what is basically a list of ingredients to make an appetising stew for their masters. I think another reason for it being so brief is that it was surely rather hard work writing on clay tablets. You couldn't waffle on as I do on my computer.

The BBC article that I read about this mentioned four recipes one of which, to my mind, was rather more sophisticated because it was a pie, which involves rather more processes. It was a pie made from wildfowl - pigeons perhaps and some kind of greens and of course somebody has had a go at that too:

A further claim, reported by Richard Nilson, a blogger writing about the history of cookbooks, says:

"It is notable, though, that the evidence suggests that it is at this time and place that cooking in liquid was first introduced. It was an innovation in cooking and supplemented the open fire roasting and closed oven baking." Richard Nilson

Really? If they were writing for experienced cooks, then it stands to reason that they had been cooking with water for some time. So who knows when that began.

“It is really fascinating to see how such a simple dish, with all its infinite variety, has survived from ancient times to [the] present, and in those Babylonian recipes, I see not even the beginnings; they already had reached sophisticated levels in cooking those dishes. So who knows how much earlier they began?” Nawal Nasrallah - Culinary Historian Yale

Technically speaking it's not the first written recipe either. That honour, so far, goes to the Egyptians, and 1950 BC when a recipe for a flatbread was written on the wall of the tomb of Senet.

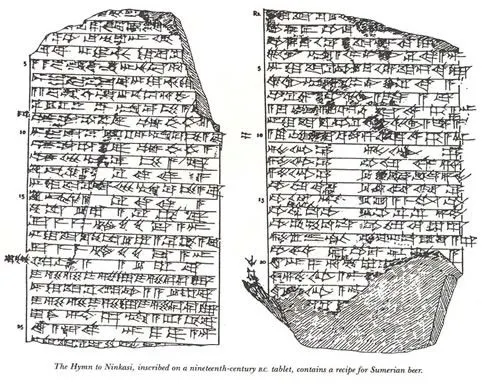

But it was just one recipe, not a collection of them. There is also another one for beer "liquid bread" written in Sumer around the same time. This one is in Oxford University's collection, and it's actually contained in a poem to the goddess Ninkasi - the goddess of beer (bappir is, I think, a mush of grain):

Mixing in a pit, the bappir with sweet aromatics,

Ninkasi, you are the one who handles the dough with a big shovel,

Mixing in a pit, the bappir with honey,

You are the one who bakes the bappir in the big oven,

Puts in order the piles of hulled grains,

Ninkasi, you are the one who waters the malt set on the ground,

The noble dogs keep away even the potentates,

You are the one who soaks the malt in a jar,

The waves rise, the waves fall.

You are the one who spreads the cooked mash on large reed mats,

Coolness overcomes,

You are the one who holds with both hands the great sweet wort,

The filtering vat, which makes a pleasant sound,

You place appropriately on a large collector vat.

When you pour out the filtered beer of the collector vat,

It is [like] the onrush of Tigris and Euphrates.

Now that involves liquid. Bread, beer, stew - pretty basic stuff and all three can be used in the same recipe.

However, those four tablets in Yale's archives are, so far, considered the first actual cookbook, because there are several recipes, written down, altogether in one place.

All of which I did not intend to write about. No - I was going to do one of my 'first recipe' pieces, but when I was searching for an appropriate beginning picture for a 'first recipe' piece I found all the above stuff, which was not only interesting, but also made me change my focus somewhat.

You see the book I chose is this one - The Continental Flavour by Nika Standen Hazelton which I seem to have bought here in Australia in 1970 but which was first published in 1961 - when I was beginning university. It's a Penguin paperback, there are no glossy pictures, just the occasional chapter heading line drawing and it's arranged in what was for then, the standard way of arranging cookbooks - beginning at the start of the meal and working your way through to dessert. Nowadays anything goes.

Because of this, I am finding, as I work my way through my collection that the first recipe often tends to be somewhat uninteresting, or at least pretty basic, with, moreover the danger of repetition. As it is in this book. The chapter is Hors d'œuvres, appetisers and salads and the first recipe is French hors d'œuvre which I have done in many guises before. Which made me leave the book lingering for some time. What more could I say? So when I found the stuff about real 'first recipes' I couldn't resist starting off with that.

So I am abandoning the actual first recipe and will just say a little about this particular book.

Well before I completely leave the first recipe I'll just quote Nika Standen Hazelton on a general, maybe old-fashioned? rule about first courses:

"the choice of how to start a dinner rests squarely with the hostess. She must observe one rule only - that the appetisers or hors d'œuvres, wherever served, be light and teasing to the palate and never filling."

Even more old-fashioned - "However, simple, they should tempt the palate, and look like a still life." Although, when I think about it maybe these days we actually sometimes think more about the appearance than the taste - it must be all those glossy pictures, TV competition, and restaurant presentation.

She's right of course, but these days we often ignore the 'filling' bit don't we? And I am a sinner here myself sometimes. For example, you may remember, I recently served, as an appetiser to my family, Ixta Belfrage's Giant cheese on toast with spring onion, honey and Urfa butter. Delicious and filling. Definitely not light.

Back in the day that first recipe was simply the first recipe in the book. It wasn't there to suck you into reading, or at least browsing, the entire book. Or indeed to suck you into buying it. I bought this particular book because I felt that my cookbook collection was lacking recipes from the non-obvious European countries - anywhere not Italy or France basically. I wasn't even attracted by the cover which is also a bit plain, or the author - I did not know her. No I think it was just the title. When books were less glossy than now I would have bought them for the author or the subject I think, and I doubt that I actually looked at the recipes much before buying.

These days, as well as those aspects, I do indeed look inside the book at the pictures and the recipes. For me it has to be more than the pictures as well because I now have so many cookbooks, that even if the pictures are glorious and the author a known factor, I do not buy if the recipes themselves are all recipes for things for which I already have countless versions. Which is a little bit why I have not yet bought Claudia Roden's latest book Med although I shall probably succumb one day.

I'm sure I have made a few things from this book but the only one that has been made a lot is this goulash which she calls Austrian veal goulash à la Richard Strauss. (It was apparently a favourite of the wife of the composer). It's a terrible photo I know - apologies. I took it for that long ago cookbook I made for my boys. But it is indeed a very delicious dish, and I must make it again soon because we haven't had it for a long time.

In fact I should probably sit down with the book to see if there is anything else that I have overlooked. For I think she is probably an overlooked author. She wrote some thirty books and several columns in various well-known publications, so obviously her publishers thought she was worth hanging on to. She was born in Rome to German/Italian parents, educated in England and Switzerland but spent most of her life in America. And I bet you have never heard of her.

I looked for recipes of hers that had been made by others, but found just two - both of which, from other books than mine, look very worth trying: Fondue Bruxelloise/ In the Vintage Kitchen - a kind of cheese croquette (she wrote a whole book on cheese) and Swiss Onion Soup / The Kitchen Scholar

"She lets you know from the onset that she assumes, if you have bought and are reading this book, you know something about cooking." Sandy's Chatter

Not a modern approach is it? Today it's all about, well almost all about, getting people who don't cook to cook. Easy, Quick, Fun, and so on. Not that her recipes are difficult - that goulash is very, very easy to make. But yes, she does assume some knowledge. She says so in her Introduction to my book. But I will say no more - just one long quote from the lady which is worth repeating and which is still relevant today:

"I have done my best to keep away from the mystique which seems to surround so much cooking nowadays. Much high-flown twaddle is written about herbs, wines, gourmets, epicures, and the like, when some of the best cooks who ever lived were and are quite illiterate and unsophisticated.

There is no mystery to food. It should be delicious wherever possible, but not a fetish. We eat to live, and there are other pleasures in life besides eating. But well prepared food is one of the greatest, and one within the reach of anybody who can read and who cares enough to take a little trouble to do things well."

Perhaps that's why those ancient Egyptians, Sumerians and Mesopotamians felt they had to pass on their skills and their knowledge as soon as they were able to actually write it down. They were the first to allow others, albeit the privileged few who could read, to learn how to cook well. However, let's not forget the very, very ancient peoples who actually invented all those skills, and who had been cooking lamb stew for generations before the Mesopotamians, but could only pass them on through show and tell.

I do wonder who first thought of throwing a bit of meat into boiling liquid. Indeed who thought of boiling liquid. When, how, why ...?

Comments